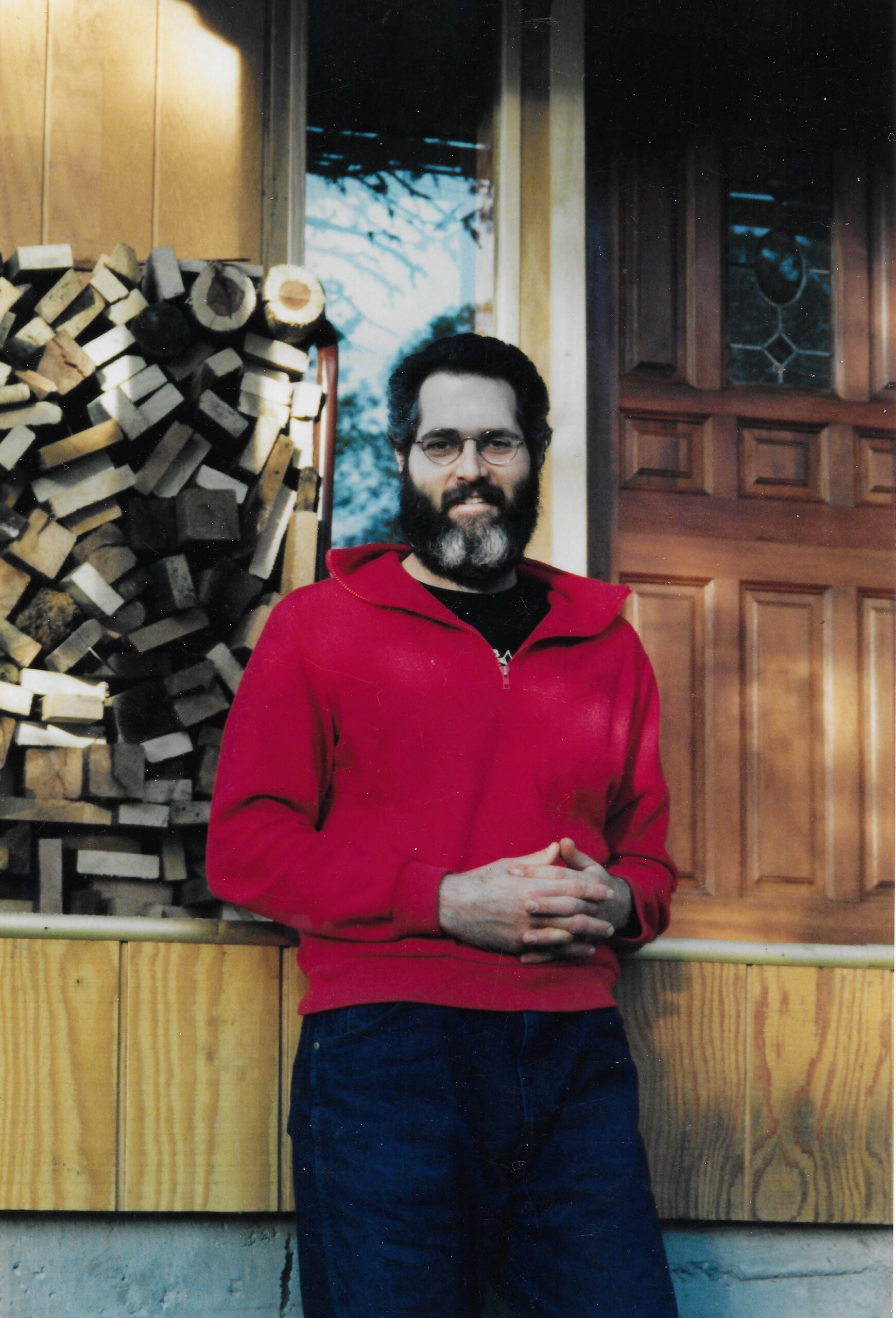

I’m sitting beside Shayna in the chemo suite. The room is sterile and over-lit. Machines whisper and hum, until they go, “ping.” A nurse comes and goes as she changes bags on the IV pole, adjusting the drip of chemicals flowing into my wife’s arm.

She is calm. Brave. Holding my hand. I’m doing my best to be steady for her, but inside, honestly, I feel the stress – squeezing my chest, pressure behind my eyes, and a hollow dent between my solar plexus and belly button.

Hospitals are a dreary venue; the smells and bright lighting mix with a low drone of angst just beneath the surface of things. There’s no escaping it.

So I decide to turn inward.

I close my eyes and breathe. Not to escape – but to enter and attend. To flow my attention not out into the worry or the fluorescent flicker, but inward – down through breath, through heartbeat, through tension – toward something quiet, subtle, deep.

It takes several minutes as my mind keeps lurching after thoughts. What will happen? What if…? I keep bringing it back.

Eventually, I find it.

It’s not the breath. Not even the heartbeat. It’s something prior to those – soft as a whisper, but unmistakably there. The unmistakable sense of being alive.

To say that it pulses throughout the body isn’t exactly right. It’s more like light through water. It’s not tied to any emotion. In fact, it exists along with the grief, the fatigue, the dread. It includes them.

And to me, it feels like joy.

Not joy as happiness. Not joy as celebration. But joy as a quiet resonance of life itself. The felt sense of aliveness. I relate to this as bodiness.

I’ve been training this awareness years before cancer barged in. But that morning, with Shayna’s hand in mine and the IV dashboard counting down the minutes of infusion, I needed it.

Mindfulness is noticing what’s arising: thoughts, emotions, sensations. Watching all that dispassionately without getting tangled. It’s a practice of awareness, of stepping back just enough to see clearly.

Bodiness is a particular twist on mindfulness.

This is stepping in. Not watching the body, but feeling it from the inside. Not observing the breath, but inhabiting the breath. Not noting sensation, but resting as sensation itself.

I call it bodiness.

It’s attending to the direct, felt sense of being alive – not as an idea, but as a texture. Yes, it is subtle. A vibration. A luminousity. An energy field. Call it what you will, it is a presence that runs through the whole body like current through water.

And when I can find it – when I settle into it deeply enough – there’s something else there.

A quiet joy. Not happiness. Not relief. But the unmistakable resonance of aliveness itself.

You can find this shimmer anywhere. Not by escaping your life, but by entering it more fully.

Start simple:

Sit. Close your eyes. Let your attention drop below thought – below story – into the body itself.

Feel the breath. Not the idea of breath, but the sensation of breath. The coolness at the nostrils. The slight lift of the ribs. The softness of the belly.

Stay with it. Let it settle you. This is familiar territory.

Then go deeper.

Feel the heartbeat. Maybe in the chest. Maybe in the neck, the fingertips, the temples, the groin. Just the pulse. The rhythmic pulse of your heart circulating blood and life-force.

Then deeper still.

Let your attention spread. Feel the whole body at once – not part by part, but as a single field of sensation. The weight of your bones. The warmth in your hands. The pressure where your body touches the chair.

Don’t look at these sensations. Feel them from the inside.

What you’re looking for isn’t peace, exactly. It’s aliveness. I am moved to call it a shimmer, vibration, pulse, field. By whatever name, it is quiet. Steady. Joyful in a way that asks nothing of you.

It doesn’t depend on circumstances. It’s not a mood. It’s closer to the truth of being alive – prior to perspective or narrative.

It’s always there.

Even in the chemo suite.

Thankfully, it’s also there.

That morning, I opened my eyes and Shayna was still on the bed holding my hand. The machines were still beeping. The nurse was still adjusting the IV.

Nothing had changed. And everything had.

I wasn’t less afraid. I wasn’t less sad. But I was more here. I was bolstered to meet the moment without collapsing under it. Supported by joy.

That’s what bodiness offers. Not escape. Not transcendence.

A quiet and subtle, unshakable joy of being alive – no matter what life is dishing you.